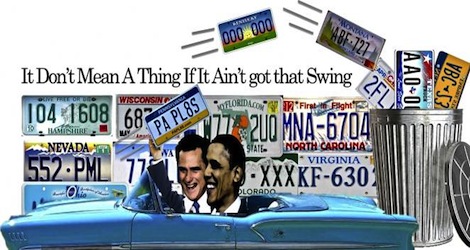

Does your vote count in the race for president? Probably not very much if you live anywhere outside of a handful of swing states. The reason: the United States’ current Electoral College system.

Does your vote count in the race for president? Probably not very much if you live anywhere outside of a handful of swing states. The reason: the United States’ current Electoral College system.

The Electoral College has been the subject of more amendments than any other provision of the U.S. Constitution. Since the 1940s, a large majority of Americans has backed moving to a national popular vote for the presidential election—about two-thirds support today, across a full range of states. As we experience an election focused on fewer states than ever before in modern history, the case for change has never been stronger—and a realistic roadmap for reform never closer than with the National Popular Vote plan that is moving in state legislatures across the country.

The current Electoral College system, grounded in state “winner-take-all” laws that award all electoral votes to the candidate who wins the most votes in that state, violates fundamental principles of representative democracy. A candidate can lose despite earning more votes, as in 2000. That has happened four times in our history, but the biggest problem is one that affects every election: the geographic gerrymander created by winner-take-all rules. Presidential campaigns today mostly ignore any state other than the few swing states where their activity might affect who wins the state and all its electoral votes.

This focus on a handful of states has perverse consequences. For example:

- Campaigns typically don’t do any national polling or any polling outside these few states, significantly limiting the viewpoints and interests that affect what the campaign does or says. In 2004, strategists in George Bush’s re-election campaign said they never polled a single person outside of 18 potential battleground states in the last two and a half years of the campaign.

- The billions of dollars being spent on the presidential race are focused nearly exclusively on affecting undecided voters in fewer than 10 states—that’s likely fewer than 1% of all Americans. A national popular vote wouldn’t remove the influence of money, but it would create new value to grassroots efforts seeking to encourage participation in all states.

- Voter turnout is sure to be different in the swing states compared to the rest of the nation. In 2004, that gap was close to 10%, and was 17% for eligible voters under 30.

- Partisans are seeking to game the outcome through abhorrent laws designed to make it harder for legitimate voters to participate because a few thousand votes can affect the outcome in a swing state. Lurking in 2013 are new efforts in Republican-run states that have been consistently won by Democrats to change from allocating electoral votes on a winner-take-all basis to doing so by congressional district. While Pennsylvania lawmakers backed down from plans to move to such a system in 2011, it remains a serious possibility as a means to tilt the scale toward one party.

- A president’s policies inevitably will be distorted as well. At the very least, presidents themselves treat states differently. Consider that, as president, Barack Obama has held 19 events in North Carolina, a swing state that he won with 49% of the vote in 2008—but he has not been to South Carolina even once despite winning 45% of the vote there in 2008. That 4% difference in vote percentage would require shifting only the vote of one in twenty-five voters—but that difference is seen as an unbridgeable chasm with the winner-take-all voting rule.

The divide between swing states and the rest of the nation looks likely only to worsen in the years ahead. The number of swing states has declined steeply over the past generation for the same reason that the number of competitive congressional districts has changed—a hardening view of the major parties among the electorate. It also means greater consistency. Every one of the nine swing states of 2012 was among the swing states of 2008—and looking to 2016, there is no evidence that any new state will move into swing state status.

Left unchanged, the Electoral College will further deepen political inequality among states, with a particularly damaging impact on rural state voters and racial and ethnic minorities, both of whom are under-represented in swing states.

Instead of this debased method of election, every American voter should have equal power to hold his or her president accountable through a national popular vote for president. With popular vote elections governing how we elect every governor and Member of Congress, we know what such elections look like. As the vote totals rise on election night, voters know that their votes are counted on an equal basis with everyone else and that, when all the counting is done, the candidate with the most votes will win.

Within the Constitution is a straightforward opportunity for reform of this kind. Laid out in detail at www.nationalpopularvote.com, the National Popular Vote plan is based on two powers granted to states under the Constitution.

The National Popular Vote Plan

The National Popular Vote Plan

First, states have exclusive power to decide how to allocate electoral votes, one characterized by the Supreme Court as “supreme” and “plenary.” Initially, few states awarded all electoral votes to the statewide vote winner—several, in fact, didn’t even hold popular elections. It was not until Andrew Jackson’s presidency that the winner-take-all unit rule based on statewide popular votes became the norm, driven by states’ partisan parochial incentives to give as many votes as possible to one candidate. The unit rule isn’t in the Constitution, wasn’t intended by the framers of our Constitution, and is most certainly not in the best interests of our nation.

Second, states have the constitutionally protected power to enter into formal, binding agreements. There are hundreds of examples, including the Port Authority and the Colorado River Compact. Fewer than a thousand words, the National Popular Vote compact establishes that participating states will award all of their electoral votes to the slate of the candidate who wins the national popular vote in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. It is activated if—and only if—the number of participating states collectively have a majority of votes in the Electoral College.

States enter the National Popular Vote compact one by one, passing a statute through regular legislative channels. If by July 2016, states adopting the compact collectively have a majority of electoral votes (currently 270 of 538), the agreement is set in stone for the year, and the White House is guaranteed to the candidate who wins the popular vote. Electoral votes still will elect the president and the total number of electoral votes won by a candidate might vary based on which states are in the compact, but no one will focus on electoral vote margins. All attention before and after the election will be on the popular vote. Gone will be the red-blue maps on election night and the early projections of winners while western states are still voting. Every vote will count the same, whether it is cast in Maine, Alaska, Texas, or Florida.

Since the plan’s launch by National Popular Vote in 2006, it has passed into law in eight states and in Washington, D.C, with a total of 132 electoral votes—nearly halfway to the 270 threshold. We’ve seen wins in both small states like Hawaii and Vermont and larger states like California and New Jersey, have been introduced in every state, earned the votes or sponsorship of more than 2,100 legislators and won the backing of the League of Women Voters, Brennan Center, Common Cause, NAACP, New York Times, Los Angeles Times, columnists E.J Dionne and Hendrik Hertzberg, former Members of Congress Fred Thompson (R-TN), Jake Garn (R-UT) and Birch Bayh D-IN) and prominent independents like Rhode Island governor Lincoln Chaffee and 1980 presidential candidate John B. Anderson.

The last time the nation had a similar focus on reforming the Electoral College was in 1969-1970. National support for a national popular vote reached 80% in Gallup polls, and a proposed constitutional amendment to abolish the Electoral College won the votes of 81% of U.S. House Members, including future presidents Gerald Ford and George H.W. Bush. It faltered in the Senate only because of parliamentary procedures denying majority support for change.

The case for reform is even stronger today. In the 1960s, far more states were contested, and there was more fluctuation in voting patterns. We are better prepared for a national popular vote, with more uniform voting standards and patterns of participation.

Addressing Objections

Addressing Objections

Objections to the National Popular Vote plan generally fall into three categories: 1) defense of the current Electoral College rules, with a kind of magical thinking that the success of the United States is connected to the Electoral College; 2) belief that the “right way” to replace the current system is by amending the Constitution; 3) support for alternative reform approaches.

Defenders of the current Electoral College present a grab-bag of arguments. They suggest fairer presidential elections might undermine federalism despite the fact that the National Popular Vote plan upholds, rather than diminishes, state powers under the Constitution and poses no threat to the U.S. Senate. They worry that the United States in the 21st century is incapable of fairly administering close popular vote elections, despite the successful examples of large states like Texas and California and large nations like Brazil. They warn that third parties will start having a much bigger impact despite the lack of evidence from the thousands of statewide popular vote elections for governor and U.S. Senate. They argue candidates will only spend time in big population states and cities even though the numbers show such a strategy would be a losing formula.

The proposal of a constitutional amendment is a diversion. Many National Popular Vote advocates support an amendment as well, but others do not. Certainly the winner-take-all unit rule system used by most states is not “more constitutional” than the National Popular Vote plan: it’s just the status quo that was adopted by the 1830s and one that, as implemented today, would shock our Founders. States nearly always have taken the lead in advancing a more representative democracy, including the expansion of suffrage rights to women and to people without property and the establishing of a popular election of U.S. Senators.

Alternate reform approaches can have zealous advocates, but are either dead in the water politically or unlikely to meet the goals of voter equality and majority rule. For example, some propose allocating electoral votes by congressional district, but FairVote’s analysis shows that, if established nationally, this proposal would have an extreme partisan bias. Both congressional district allocation and proportional allocation of electors within states would keep many states sidelined—and trying to pass these reforms state by state is problematic and prone to partisan gaming of the national rules.

With a national popular vote, presidential campaigns would seek votes everywhere in a true 50-state effort. Every vote—in every corner of every state—would be equal. Americans could get seriously involved in presidential campaigns in their own communities. The bottom line is that candidates for our one national office should have incentives to speak to everyone, and all Americans should have the power to hold their president accountable.

As we enter the final weeks of the 2012 campaign, it’s a great time to ask your state legislators to be leaders in pushing for the National Popular Vote plan in your state. For resources on getting involved, visit NationalPopularVote.com and FairVote.org.

ACTION: Tell your legislator to support a national popular vote for President

Read about other threats to democracy in the complete series, “Seven Sins Against Democracy”

Rob Richie has served as the Executive Director of FairVote since 1992. His writings have appeared in the nation’s leading newspapers and in nine books, including as co-author of Every Vote Equal about establishing a national popular vote for president and of Whose Votes Count about the case for proportional voting and ranked choice voting. He has been a guest on NPR’s All Things Considered and Talk of the Nation, C-SPAN’s Washington Journal, NBC News, CNN, FOX, Bloomberg News, Democracy Now and MSNBC and addressed conventions of the American Political Science Association, National Association of Counties, National Association of Secretaries of State, Free Press, National Latino Congreso and National Conference of State Legislatures. He serves on the Haverford College Corporation. He and his wife Cynthia Terrell have three children.

Rob Richie has served as the Executive Director of FairVote since 1992. His writings have appeared in the nation’s leading newspapers and in nine books, including as co-author of Every Vote Equal about establishing a national popular vote for president and of Whose Votes Count about the case for proportional voting and ranked choice voting. He has been a guest on NPR’s All Things Considered and Talk of the Nation, C-SPAN’s Washington Journal, NBC News, CNN, FOX, Bloomberg News, Democracy Now and MSNBC and addressed conventions of the American Political Science Association, National Association of Counties, National Association of Secretaries of State, Free Press, National Latino Congreso and National Conference of State Legislatures. He serves on the Haverford College Corporation. He and his wife Cynthia Terrell have three children.

This is a really interesting article. It is amazing yet in 1969 representatives mostly agreed to change the rules and that nothing happened !

I hope the National Popular Vote plan is in place by 2016’s election. I’m tired of the candidates pretending like we live in the United ‘Swing’ States. The Electoral College is obviously outdated, and actually reinforces the inadequacies it was supposed to prevent – candidates only caring about a few states.

I agree with Penelope and Sara, we are in the 21st century and the US is supposed to be one of the most developed democracy whereas the electoral college appears to be a very old fashion way to elect the president. It reminds me former electoral rules in Europe when you did not have an universal right to vote !