Marcia Mount Shoop Responds to Rachel Mastin’s Review of Touchdowns for Jesus

Read Rachel Mastin’s Review of Mount Shoop’s book here.

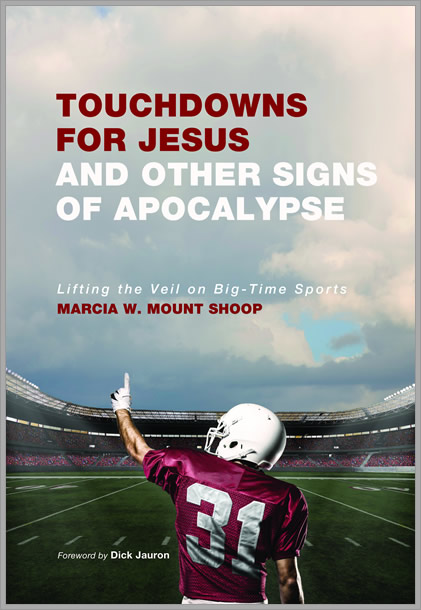

I am grateful for the time that Rachel Mastin took with my newest book, Touchdowns for Jesus and Other Signs of Apocalypse: Lifting the Veil on Big-Time Sports. My prayer for this book was that it would elicit a deeper conversation about sports and American society’s most pressing issues. Mastin’s review is an opportunity to have exactly that kind of conversation.

Mastin and I have some things in common — we are University of Kentucky basketball enthusiasts, and we work with survivors of domestic and sexualized violence. We also both have vocational identities wrapped up in the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.). And, like Mastin, I have spent more than my share of time watching football games on TV.

Unlike Mastin, however, I do not classify myself as a sports fan. I am a football coach’s wife, and that is a qualitatively different orientation to the game. I describe some of these dynamics in my book. Also, a profoundly formative part of my identity is that I am a survivor of rape, abuse, and stalking. I hope that Rachel does not have that experience in common with me, although it wouldn’t be a shock if she does, since sexual violence is a common experience for women in this country (about one in four women experience it).

___________________________________________

The fact that my book is not what Mastin expected to be is actually really good news to me.

___________________________________________

It is important to add in this context that the sexual violence I suffered was perpetrated by a star football player in my hometown. And he “got away with it” under the noses of a lot of people who witnessed his abusive behavior, including school officials, football teammates, and friends. And those crimes will never register on any statistical Richter scale since I did not report it to the police. In fact, it was a secret I kept and was deeply ashamed of for years. I am like most survivors: my rape went unreported and unpunished.

I share this personal fact (as I did in my first book, Let the Bones Dance: Embodiment and the Body of Christ) because I want to emphasize that the exclusion of the perspective that Mastin wished I had dealt with is not there for a reason. And herein lies the wonderful opportunity that she has given us to have a deeper conversation.

I share this personal fact (as I did in my first book, Let the Bones Dance: Embodiment and the Body of Christ) because I want to emphasize that the exclusion of the perspective that Mastin wished I had dealt with is not there for a reason. And herein lies the wonderful opportunity that she has given us to have a deeper conversation.

Mastin explains in her review that I left out attention to the problem of “entitled athletes.” She shared a story about a particular quarterback and his pick-up line with women to get sex. One woman who had rebuffed his advances described him as a “jerk.” She went on to say that I was “irresponsible” to leave out any attention to “the consequences that this sense of entitlement and power… has for the way players learn to interact with other people in their lives, especially women.”

Mastin’s story is a familiar one in the American conversation about big-time athletes. I have heard it a lot through the years—about the way a player acted in class, the way a player walks around campus, the way professional players flaunt their wealth, the easy way people call players “thugs,” and the list goes on and on. I hear Mastin saying that she expected me to deal with this familiar narrative in my book. The fact that my book is not what she expected to be is actually really good news to me. My goal was to get underneath the familiar narratives and to get to a deeper space for conversation.

___________________________________________

I didn’t write about the narrative of the entitled athlete because I believe that the underside of that story is where the problem actually lies.

___________________________________________

One reason I didn’t deal with the familiar narrative of the entitled athlete is that, with twenty-plus years of interacting with football players as a coach’s wife, I have come to believe that the “entitled athlete” is a figment of people’s perceptions. I experience it as a caricature and stereotype that does not apply to almost all of the players I know. I have not just interacted with these players as an observer on game day: I have had them in my home, I have listened to them when they’ve had problems, I have prayed with them when they got injured, I have watched them play with my children, and I have fed them meals. I have met their families – their girlfriends and wives, and in some cases their children. Of all the players we have interacted with through the years, I can honestly say that almost none of them fit the description Mastin shares in her story about the jerky quarterback.

In short, I didn’t write about the narrative of the entitled athlete because I believe that the underside of that story is where the problem actually lies.

In short, I didn’t write about the narrative of the entitled athlete because I believe that the underside of that story is where the problem actually lies.

Many football players actually come from a radically different place than a sense of entitlement. Many of them don’t feel entitled because they have never had much to start with in their lives. Many football players are good soldiers who want to do well so that they can make their lives better. There is the occasional player who is very immature or overly impressed with himself (which is usually a veil for a deep insecurity), but generally the players we’ve been around are solid and earnest young men who we are thankful to know.

People in the church won’t want to hear this, but I’ve met more men with a dangerous sense of entitlement who make their living preaching sermons on Sundays than I have among the ranks of football players. I would also add that the Church doesn’t do a great job of holding these men accountable, either. In fact, in many of the worst cases, clergy perpetrators get passed off to another community of people who misplace their trust in them under false pretenses.

___________________________________________

In the football world, I would argue that the sense of entitlement is much more prevalent among the people with the most power (and money).

___________________________________________

In the football world, I would argue that the sense of entitlement is much more prevalent among the people with the most power (and money)—the team owners, the general managers, wealthy alumni (who often never played a snap of football), and some head and assistant coaches.

Mastin is correct that there are familiar tales of players “getting away with things,” including sexual violence. And we can say the same thing for fraternity boys, politicians, entertainers, and some other affluent males who have been able to buy their way out of being punished for criminal actions. We have a power problem in this country, and it is tangled up with masculinity and other embodied markers of power and privilege. At the heart of it all, my book is about power and the use and abuse of it in sports. In my experience, the most pressing and the most distorted areas of abuse of power are in the places we most often fail to look.

Players who do get away with behaving badly do so most times because someone with power needs them to not get in trouble so they can perform their magic at game time. Florida State University’s handling of the Jameis Winston case is the perfect example. Had Jameis Winston, a black male in America, run afoul of the criminal justice system and he wasn’t an FSU football player, the outcome for him would undoubtedly have been different. Winston was able to avoid even making a statement for years after he was accused of sexual assault because he is a really good football player and those who have a stake in him protected him.

While it may appear on the surface to be a sense of entitlement on Winston’s part, he could only acquire this seeming invincibility because the true power brokers have a lucrative use for him. And as soon as his usefulness is gone, so goes his protection. This lack of accountability for some players reminds me of the practice of passing “hard to manage” black boys through our public school system even though they are not reaching levels of proficiency and learning. This double standard is not a privilege; it is a dismissal of their worth as human beings.

___________________________________________

Players who do get away with behaving badly do so most times because someone with power needs them to not get in trouble so they can perform their magic at game time.

___________________________________________

The same dangerous practice could be said about the Ray Rice case. Make no mistake: short of TMZ airing the elevator video of his punch, Ray Rice was not going to be punished by the NFL for what he did that night. They needed him on Sundays to gain big yardage and keep the money rolling in. The NFL banished him from their ranks because he had become bad news for them. Can you see how easy it is for those with power to protect and then to discard? That is one of the central problems that I wanted to unveil—power is racialized and sexualized in this country in stealthy and deceiving ways. The world of big-time sports holds a mirror up to American culture when it comes to these dynamics in sometimes startling ways.

It is not easy to be called “irresponsible” when you are a full-blooded Presbyterian like me! However, the more healing I experience in my journey with sexual violence, the less I feel I am responsible for saying or doing it all. My prayer is that I can practice being response-able, that is, being able to respond with a healing intention.

In big-time sports, the commodification of people is the most annihilating demon I encounter on a regular basis. It shows itself in different ways on the surface, but deep down it’s about people not being able to take up life-giving space as human beings in this world—jerks and all.

_____________________________________________

AUTHOR BIO: The Rev. Marcia Mount Shoop, PhD is a theologian, minister, and author who lives in West Lafayette, Indiana. She blogs at www.marciamountshoop.com and you can follow her on Twitter @mmountshoop.

Read Rachel Mastin’s review of Mount Shoop’s book here.

Read more articles from this issue, “Hearing the Voices of Peoples Long Silenced”: Gender Justice 2014!