View article in PDF (optimal for printing)

View article in PDF (optimal for printing)

“As for those who in the present age are rich … They are to do good, to be rich in good works, generous, and ready to share, thus storing up for themselves the treasure of a good foundation for the future, so that they may take hold of the life that really is life.”

—1 Timothy 6:17-19

We are aging soldiers an ancient war.

Seeking out some half remembered shore

We drink our fill and still we thirst for more

Asking, “if there’s no heaven, what is this hunger for?”

—Emmy Lou Harris, The Pearl, “The Pearl,” (Nonesuch Records, 2000).

“Whatever I had read as a child about the saints had thrilled me. I could see the nobility of giving one’s life for the sick, the maimed, the leper. But there was another question in my mind. Why was so much done in remedying the evil instead of avoiding it in the first place? Where were the saints to try to change the social order, not just minister to the slaves, but to do away with slavery?”

—Dorothy Day

Scene: Playground

Young Girl reading a book about knights

Girl: What does our family crest look like mommy?

Mom: Poor people being crushed by boots.

—The Reader’s Digest, “Life’s Funny that Way” (May 2011), 81.

Capitalism and Christianity: Compatible World Views?

One question emerges over and over again among congregations and Christian ethicists: Is the economic theory underlying modern capitalism Christian? Are its ethical principles compatible with the Christian worldview?

Despite many claims to the contrary[1] (by those who believe capitalism’s freedoms are not only historically derived from a Christian worldview, but also conducive to the nurture of the freedom God wishes to bestow on all people), the short answer is that intrinsic to the Christian worldview is a fundamental critique of capitalism. Certainly from my on-going private sector experience—longer than my professional church and non-profit experience—I see the limits of making the market lord and definer of human hopes.

There are three primary reasons I see for this intrinsic tension, even over and against the many Christians who openly promote the idea that laissez faire capitalism is “God’s preferred economic system.”[2] The first is that capitalism does not share Christianity’s understanding of the ends of human life. The second, and related, reason is that capitalism does not share with Christianity a common understanding of the nature of human beings. Finally, and again tied into the other two, is that capitalism does not share Christianity’s understanding of work as vocation. It understands work as a mere factor of production, rather than as a primary way for participating in the life of God and contributing to the common good.

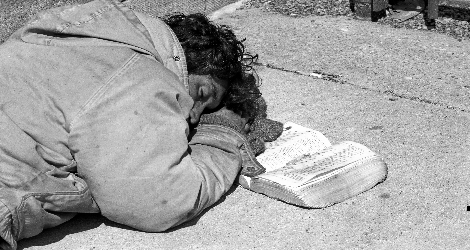

These differences mean that, unless there are those in the Church who can articulate very real limits for presently unfettered markets, we will continue to condone through our silence a misguided idolatry. We will continue to condone the heresy that markets can care for us, our neighbors, and God’s creation just as well as we can through our constant participation in democratically elected governments, our involvement in the institutions of civil society, and our grounding in Christian communities committed to exposing idolatries rather than abetting their perpetuation. Ultimately, the Church’s failure to recognize and call out this idolatry has prevented Christians from presenting a common front of solidarity with the marginalized when political and economic policies consistently favor the interests of accumulated wealth over the interests of a more broad based concern for community health.

I regret to say that I find Reverend Owen’s article frustrating. It would have been helped if she had started with a definition of capitalism. An acknowledgement of different types of capitalism would have clarified that her real beef is with totally laissez faire markets. One could then ask whether this is the political-economy we have, or whether it is an ideology vying to reshape our common life. This would have strengthened her argument which seems more oriented to reforming capitalism rather than replacing it with some other economic system.

She names Max Stackhouse as a defender laissez faire. She can only do this because she seems to have no idea what he affirmed or why. The choice, Stackhouse says, is between locating the economy in the family, the state, or the social space between them that had been carved out by the church – corporations. Separating the economy from the state allows states to engage in the sort of regulation she suggests in her conclusion.

Her characterization of is also unfair because Stackhouse brings considerable theological and ethical resources to bear to critique and humanize capitalism. Indeed, this is the church’s vocation! Engagement with his ideas would have clarified Owen’s muddle on the relationship between economics and theology. In all of this his is closer to a “New Deal” affirmation of capitalism than laissez faire. And so is she!