How would our churches and our prophetic ministry be different if we looked to God’s creation as a judge for what is appropriate and what is not?

By John R. Preston View and Print as PDF.

View and Print as PDF. One Sunday, as an afterthought to Earth Day, I read a short statement from James Gustave Speth’s The Bridge at the Edge of the World during the Concerns time of worship that normally precedes the prayers of intercession. My reading had captured the gist of Speth’s thesis that our world’s capitalistic growth economy has led us to a point whereby the planet is ecologically unsustainable. We see this in many ways but certainly in earth warming and climate change that bring more frequent and devastating storms, among other environmental and social disasters.

One Sunday, as an afterthought to Earth Day, I read a short statement from James Gustave Speth’s The Bridge at the Edge of the World during the Concerns time of worship that normally precedes the prayers of intercession. My reading had captured the gist of Speth’s thesis that our world’s capitalistic growth economy has led us to a point whereby the planet is ecologically unsustainable. We see this in many ways but certainly in earth warming and climate change that bring more frequent and devastating storms, among other environmental and social disasters.

A week later, I found out that someone in the congregation had objected, and the Session agreed that my reading was “inappropriate.” I was told that what I had read was appropriate for an adult education class, but not for worship. The Session was concerned to head off a precedent of congregation members using worship as a forum on social issues.

It is a complex question: what is appropriate for worship? Obviously some things are not appropriate, and it is the Session that has the responsibility to make that judgment. Yet what factors go into making a faithful decision about what is appropriate? And when different ideas emerge, to what—or to whom—do we look to mediate that conflict? Might that mediator or judge be something that transcends us all?

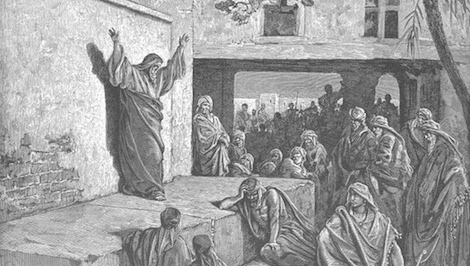

In the prophet Micah there is another court, one that is mythological. Micah accuses in this court the rulers, the priests, and the prophets, saying:

Her rulers sell justice, her priests give direction in return for a bribe, her prophets take money for their divination. (Micah 3:11a)

Micah goes on to describe in graphic terms what the leaders are doing to the common people:

You hate good and love evil,

you flay men alive and tear the very flesh from their bones

you devour the flesh of my people, strip off their skin, splinter their bones;

you shred them like flesh into a pot, like meat into a cauldron. (3:2-3)

Again, a court must decide on a judgment. Yet this time there is a reversal. The elders of the people are the defendants. Who then is the prosecutor, who the judge? Listen:

Up, state your case to the mountains; let the hills hear your plea.

Hear the Lord’s case you mountains, you ever lasting pillars that bear up the earth; for the Lord has a case against his people, and will argue it with Israel. (6.2)

The prosecutor is God, but the Judge is creation itself!

How would our churches and our prophetic ministry be different if we looked to God’s creation as a judge for what is appropriate and what is not? Or, to ask it another way, What does it mean to be faithful to our Creator in our time on this great earth?

We must deal with two dis-connects. The first is the most obvious: the disconnect between a sustainable earth and the secular god of prosperity, rampant consumerism, and economic growth. The second is less obvious. It is a problem within the church: a disconnect between redemption and creation, between worship and morality.

Both disconnects are kept in place by the traditionalism of the church which has, I will argue, stepped away from the prophetic role of social analysis and spiritual discernment.

It is to these we turn.

Theologian Douglas John Hall, in his three-volume work Christian Theology in a North American Context, suggests the character of our cultural context. He sees a secularized culture infected with a loss of certainty that has become more and more nihilistic, struggling to affirm meaning and purpose in modern life. We are momentarily terrified by the bare face of such nihilism in the senseless act of a shooter who enters a movie theater as the Joker character in the latest Batman film, and shoots to kill and maim with paralyzed consciousness. But soon after, suggests Hall, the protective veneer of good old American optimism will cover up the dark existential reality. The old tried and true narratives will be put back in place. As we repress the darkness of post-modern life, nihilism becomes, in our American context, says Hall, “covert.”

How does the contemporary church fare in such a cultural context?

In a secular culture we have become, in spite of our mainline establishment status, sectarian. Because caring and love is the last defense against nihilism we have tried to become the extended family to our members. We have played the pastoral card drawing a spiritual boundary around our “family.” In this process we have drawn back from any word of prophetic challenge for fear of disturbing family unity. And, we have become a less engaged sect.

But it’s not that we have simply refrained from addressing social issues. We have refrained as well from addressing the spiritual issue of covert nihilism. Our theology is stuck in the last century. Our worship idiom speaks in archaic tongue. It is a language that no longer speaks meaningfully to our plight. Some of us accommodate it by translating the archaic idiom into another idiom that we construct in our own heads. But many put up with it in order to remain part of the family of faith even though it may be meaningless and even boring. Worship leaders dare not speak in new tongues. This, they think, might disturb the family. The net result is a worship idiom that refuses to challenge the deeper secular nihilism that nags at our communal soul. The church, in other words, is playing into the hands of covert nihilism. As Douglas Hall puts it:

Covert nihilism thrives on nothing so much as sentimental, positive religion. Christianity that rehearses all the predictable values of middle-class existence, examines only a few private sins and offers the comforts of religion for every hurt is perhaps the most effective agency of repression at work in North America today. (294, Professing the Faith)

The problem is that we deny the weakness of our master narratives whose purpose is to secure personal meaning and purpose because we dread both emptiness of meaning as well as our being labeled as pessimists in an optimistic American culture. We double down on illusionary narratives out of anxiety and fear, only to trap ourselves further in the judgment of creation.

What can we do?

We must challenge the repression. And that means taking a very hard look at our own religious tradition and the ossified traditionalism that has locked us into being a repressive force instead of a blessing. The people in the time of the Old Testament prophets knew about justice. It was a justice about land and people and, though every seminary graduate knows it is there in the heart of the Bible, it is seldom preached in our churches.

In short, the prophetic church must challenge the unsustainable growth narrative, as well as its own traditionalism, as it moves toward a saving narrative of ecological justice.

Our Creator is a God of Eco-Justice. Within the covenant between God and Israel there was a deep concern for the widow and the impoverished that reflected God’s own concern for the welfare of the “least of these.” There was also a concern for the land, which was the foundation for sustainable living. Today, for those who have the eyes to see, the plight of all creatures is tied to the welfare of the planet earth. The eco-justice story is also the earth story. It is this story that must come from a dim background, kept in place by the illusion of old narratives that are no longer viable, to the foreground of our consciousness as American Christian people. Bringing that story into the foreground of our consciousness is the prophetic task. It is also the true pastoral task in a time that struggles for meaning.

Read more articles like this one in the Nov 2012–Jan 2013 issue, “Hope for Eco-Activists: Discovering an Environmental Faith“

John Preston is a retired UPUSA minister and the previous northeast representative on the Presbyterian Earth Care steering committee. He is the author of WRESTING UNTIL THE DAWN: The Fight for Biblical Justice in a Postmodern World, and is working on a memoir that reflects prophetic ministry as his North Star throughout his career. He is a graduate of Yale Divinity School and practiced as a marriage and family therapist with a master’s degree from Syracuse University after his retirement from parish ministry. He resides in upstate New York with his wife Sally.Banner graphic, “The Prophet Micah,” by Gustave Doré.