Question: “Why should European-American Presbyterians in the United States include world music in our worship?”

I love a good mashup; I suspect we all do. There is something powerful about the collision of two different songs, a mess of lyrics and melodies that seem to work together while simultaneously offering some degree of resistance to this mating. In essence, it works so well because it doesn’t quite work. Whether it’s the place where the chords in DJ Schmolli’s “Titanium/500 Miles” mashup don’t quite align, or when Naya Rivera pleas not to be forgotten while a chorus of women behind her repeats simply, “rumor has it” in the memorable Glee mashup of Adele’s “Someone Like You” and “Rumor Has It,” or even the moment in “I Bind Unto Myself Today” (Glory to God #6) when the penultimate verse storms in with a new key, meter, tempo, and melody from what preceded it, the brilliance of a good mashup is where the material doesn’t quite line up, where two different narratives try to maintain their independence even as they reveal their own universality.

So, why should Presbyterian churches of European-American tradition include world music in their worship? The cultural reasons are clear. One of the most powerful ways to stand alongside our sisters and brothers in churches around the world is to sing what they sing. When we perform the rhythms, words, and phrases of a culture different from our own, we embody something of what it means to be them. It reminds us of what we already know: that there is a whole world of Christians with worship and practices that are quite different from our own. An infusion of musical diversity in our worship is a wonderful way to practice the diversity of God’s Kingdom, whether this diversity is reflected in the population in the pews or not. And, if a congregation is ethnically homogeneous, an ethnically diverse musical repertoire can serve as part of a foundation for growing to be a more diverse congregation.

But, what if we think about this musical diversity purely as a musical venture? Most PC(USA) churches have lots of trappings of the European-American tradition: pianos, guitars, choirs, pipe organs, and congregations raised on “God of Grace and God of Glory” (#307). Do “Thuma Mina” (#746) or “Si tuvieras fe” (#176) really have a place in this context? Do our European-American churches have a right to sing this music? How do we respect the traditions that generated this music that is foreign to us? How do we strive towards authentic renderings of these repertoires, and what happens when we fall short?

___________________________________________

There is something powerful about the collision of two different songs, a mess of lyrics and melodies that seem to work together while simultaneously offering some degree of resistance to this mating. In essence, it works so well because it doesn’t quite work.

___________________________________________

From my experience at Ginter Park Presbyterian Church and at Union Presbyterian Seminary, I think the solution is to glory in the misalignment. I remember singing “Uyai Mose” (#388) in a very powerful way at a conference at the Calvin Institute of Christian Worship several years ago, led by drums and singers in an informal worship space. When we decided to use it as an opening hymn at Ginter Park, I longed for some of the same rhythmic impact that I had encountered at Calvin, but I realized that our formal sanctuary would offer some challenges in making this happen.

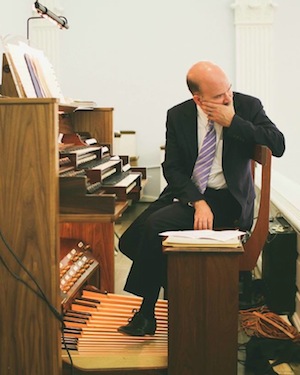

We have a capable drummer and a pair of humble Ghanaian drums in our choir loft. I decided to lay down a simple drum track with a synthesizer to cover some of the low and high frequency percussion sounds like shakers and deep djembe tones; this would help to give us the sound and impact of multiple percussionists and would free up our sole drummer to play a more improvisatory role in the piece without having to supply the basic rhythm for the hymn. As for me, I turned to the instrument that we use to lead nearly all of our worship music, our pipe organ. There is a tendency to step away from the pipe organ whenever we delve into non-Western musical traditions, but the pipe organ is much more versatile than many of us think. I decided to use the trumpet and trombone stops on the organ, stops that speak clearly and forcefully. When combined with the percussion, the organ became a kind of Zimbabwean brass band, matching the drive of the real and synthesized drumming. The result is far from perfectly authentic, but I think we managed to capture some of the spirit of the original.

I played a wedding at Union Presbyterian Seminary several years ago. I was asked to hire a couple percussionists for the ceremony, ones with significant training in Ghanaian and Latin percussion techniques. For this particular couple, I recommended the use of lots of congregational music, feeling that the room full of enthusiastic singers would be the best way to create music for the celebratory mood of the service. For the recessional piece, we started with an extended percussion duet: one player on the bongos (one of the most difficult drums to play convincingly) and another on a hand-carved kpanlogo drum from Ghana. We moved from this into a rousing singing of “Come Thou Fount of Every Blessing,” (#475) led again by drums and pipe organ. In this case the drums were the invited guest to the repertoire, but they found a place in this early American hymn tune, driving the repeated rhythm in a way that the organ would struggle to do alone.

___________________________________________

Singing music from other cultures reminds us of what we already know: that there is a whole world of Christians with worship and practices that are quite different from our own.

___________________________________________

Glory to God puts an extraordinary variety of global music on our tables. I encourage musicians, pastors, and congregations to grapple with this music, to learn what they can about how to perform it authentically, and to seek the spirit of it as they sing it in worship. I also encourage these same musicians, pastors, and congregations to love and honor their own traditions, cultures, and histories, and to find ways to revel in what happens when their own musical cultures collide with those of other places and times. I feel certain that these mashups of culture and tradition will lead to exciting new sounds and changed congregations. Glory to God!

*****

AUTHOR BIO: Douglas Brown is the music director at Ginter Park Presbyterian Church and at Union Presbyterian Seminary. In addition to directing choirs and accompanying services at both places, Doug is an avid arranger and occasional composer of music for worship and a parent to six children. His most recent endeavor “glorying in the misalignment” – a mashup of Mumford and Sons’ “I Will Wait” and “Of the Father’s Love Begotten” (#108 in Glory to God) – can be found here.

AUTHOR BIO: Douglas Brown is the music director at Ginter Park Presbyterian Church and at Union Presbyterian Seminary. In addition to directing choirs and accompanying services at both places, Doug is an avid arranger and occasional composer of music for worship and a parent to six children. His most recent endeavor “glorying in the misalignment” – a mashup of Mumford and Sons’ “I Will Wait” and “Of the Father’s Love Begotten” (#108 in Glory to God) – can be found here.

More from Advent II: LOVE in the Context of Multiculturalism.

Read more articles in this series.